The Soviet Union’s intervention in Afghanistan is widely seen as one of the most costly and misguided military decisions made in the 20th century, and it is often cited as one of the biggest reasons the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991. In his book Russia: A History, Gregory Freeze notes that the “coup de grace for detente was the decision to intervene in Afghanistan in December 1979. Ever since a Marxist faction seized power in April 1978, Moscow had given strong support to the regime in Kabul and its social and cultural transformation” (445). Conclusively, this decision proved to be catastrophic in which the “Soviet Union found itself snared in a military quagmire that consumed vast resources, cost enormous casualties, and had a devastating effect on the Soviet Union’s international position” (Freeze, 446).

In his essay Invasion of Afghanistan, James von Geldern notes that the “war, fueled by and fueler of Cold War anxieties, operated on the law of unintended consequences. Plans for a minor palace coup did not consider the possibility of a long-term war between peoples.” Further, the “war provided a divisive issue right when the dissident movement was at its peak, and diverted funding from the stagnant civilian economy as it ground to a halt. It destroyed the already ailing relationship with the western nations, and undermined Soviet relations with the Third World. Following the bizarre logic of the Cold War, in which the enemy of my enemy is my friend, it caused the United States, recently rocked by the Islamic revolution in Iran, to become an ardent supporter and arms supplying [sic] to the Islamic revolt in Afghanistan.”

In his article entitled Afghanistan: A DIFFICULT DECADE, Political Commentator A. Bovin asks several rhetorical questions about the Soviet involvement in Afghanistan that ring eerily true in the context of American involvement in Afghanistan following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Writing in 1989, Bovin states that judging “from the information [he] had, the situation in the country was becoming increasingly critical. The same ‘damnable’ questions kept coming to mind. Why weren’t the people who seized power in April 1978 able to use that power, after securing the people’s and peasants’ support, to wrest Afghanistan out of its backwardness and to rebuild the society on a new and just basis? Why did the enormous and comprehensive assistance provided by the Soviet Union, including the dispatching of a 100,000-man army, fail to lead to a strengthening and stabilization of the post-April political regime?” It is truly a historical anomaly that a small, mountainous, disjointed country like Afghanistan was able to largely withstand the pressure of the two superpowers the world has ever seen; both nations learned a costly lesson that if you attempt to impose a way of life or government on a region that is not receptive to it, massive costs will result.

To conclude, I would like to link to a song entitled “In the Afghan Mountains” by Aleksandr Rozenbaum; this song expressed the misery and grim determination of patriotic soldiers fighting what they knew to be a senseless war. Just like the events that sparked Rozenbaum’s song, American involvement in the Middle East and Central Asia created a wave of songwriting in response to the events, with hits like Toby Keith’s “American Soldier” and Linkin Park’s “Shadow of the Day” expressing both the patriotism and contempt that Americans were feeling during their own time at war. While during both Russia and the United States’ conflicts in Afghanistan each country supported opposition forces, both countries’ citizenry experienced similar sentiments which shows the commonalities of war and the effects it has on populaces.

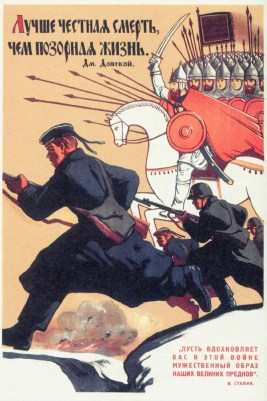

This post earned a “red star” award from the editorial team.

This post earned a “red star” award from the editorial team.

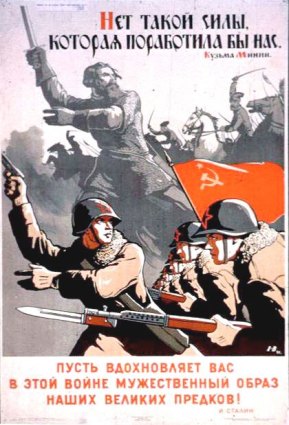

This post earned a spot in “Comrade’s Corner” from the editorial team.

This post earned a spot in “Comrade’s Corner” from the editorial team.

This post earned the “student choice” award from the class.

This post earned the “student choice” award from the class.

This post earned a spot in “Comrade’s Corner” from the editorial team.

This post earned a spot in “Comrade’s Corner” from the editorial team.

This post earned a spot in “Comrade’s Corner” from the editorial team.

This post earned a spot in “Comrade’s Corner” from the editorial team.